Research-Methods

Our Research Methods

Genealogical research combines classic record work with historical geography and archive-based source analysis. Because jurisdictions, borders, and place names changed frequently, successful research is usually the result of a structured methodology rather than a single “best” record set. Below are seven core methods we use regularly when tracing families and proving connections in this region.

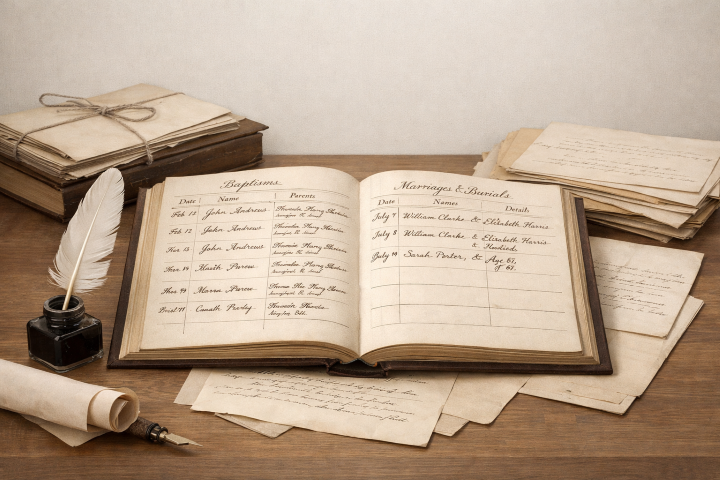

1) Church Records (Parish Registers)

For most areas of Central Germany, parish registers are the primary source for vital events before the introduction of civil registration. This includes baptisms/christenings, marriages, and burials, often supplemented by confirmation lists, communion registers, and parish “souls” or household lists where available.

Our approach is systematic: We extract all relevant entries for a surname (and its variants) across multiple decades, then reconstruct family groups and link them across generations. Witnesses, sponsors (godparents), and marriage witnesses are evaluated as part of the evidence, because they frequently reveal kinship ties, migration within a parish district, or the correct identity when several people share the same name.

Where handwriting, abbreviations, or Latin/German terminology complicate interpretation, we apply paleographic reading strategies and cross-check events (e.g., baptisms against later marriages and burials) to confirm that each record belongs to the correct individual.

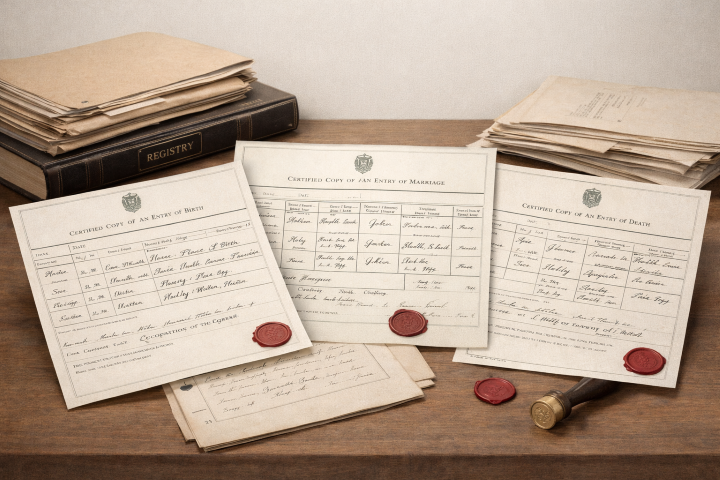

2) Civil Registration and Municipal Records

From the late 19th century onward (the exact start depends on the territory), civil registration records become central: birth, marriage, and death certificates often contain more standardized details than church entries and can provide decisive clues to parents, places of origin, and prior residences.

We pay particular attention to margin notes, supplements, and supporting documentation (where accessible), such as attachments to marriage records or later amendments that reference earlier events. We also use municipal sources—population registers, resident registration files, citizenship lists, and address books— to track families between life events and to identify when and where a move occurred.

This method is especially effective for confirming identities, resolving conflicting data, and documenting family lines into the modern period with a clear, evidence-based trail.

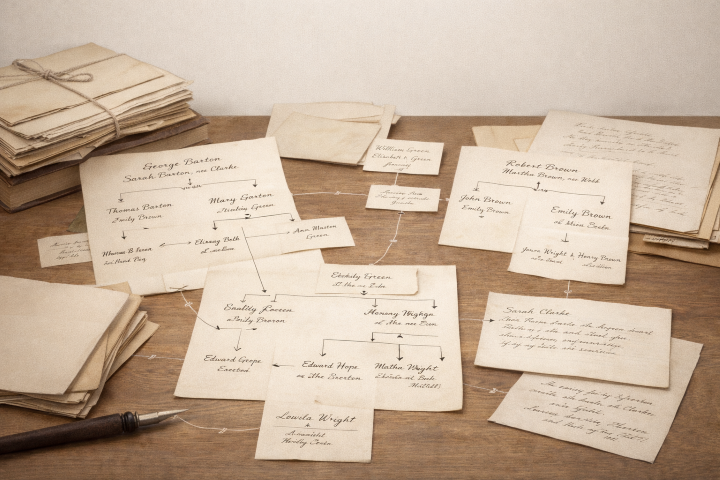

3) Reverse Research and Cluster (Network) Analysis

When a direct record does not clearly identify a hometown or parentage, we expand the research focus beyond the target person. This method—often called reverse research or cluster research—examines the broader social network that appears in the records: relatives, godparents, marriage witnesses, neighbors, coworkers, travel companions, and individuals with the same surname in the same area.

The goal is to reconstruct patterns: repeated witness names, recurring villages, occupational links, and intermarriage between families often indicate the correct parish or origin. In Central Germany, this is particularly useful because small communities frequently share surnames, and people often moved between nearby villages while remaining connected through church and family networks.

Cluster analysis can also be combined with migration research (including emigration to the U.S.) by tracking groups who left around the same time or settled in the same destination area, which can lead back to a specific origin parish.

4) Historical Geography: Jurisdictions, Borders, and Finding the Right Place

A major challenge in Central German genealogy is that modern place and state concepts rarely match the historical reality of earlier centuries. Territorial borders changed, administrative structures were reorganized, and ecclesiastical jurisdictions (parishes and church districts) did not always align with civil administrations.

To avoid searching in the wrong place, we work with historical maps, gazetteers, and period-specific administrative frameworks (such as former districts, “Ämter,” lordships, and parish jurisdictions). This also includes identifying incorporated villages, abandoned settlements, and places that existed historically but no longer appear on modern maps.

This step is essential when clients only know a broad region (e.g., “Central Germany” or “Saxony”), when a place name appears in multiple locations, or when U.S. records contain phonetic spellings that need to be matched to historical German place names.

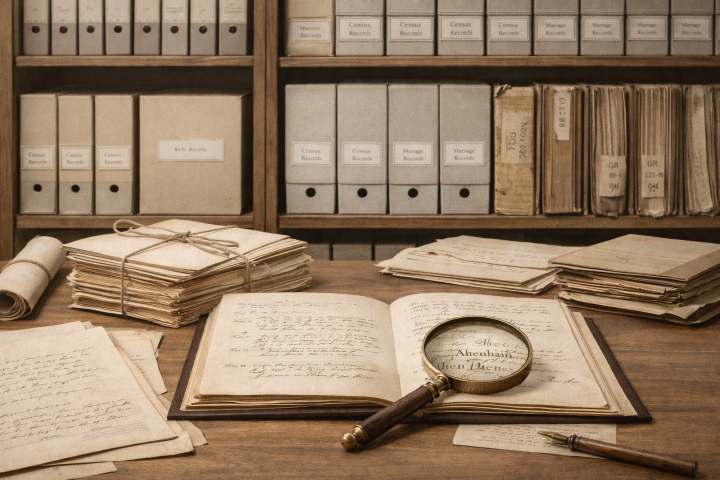

5) Archive Research: State, Church, and Local Archives

Many crucial sources are not available online or require targeted archive work. Depending on the locality and time period, relevant materials may be held in state archives, church archives, municipal archives, or specialized collections. We use archival catalogues, finding aids, and inventories to locate the correct record groups efficiently.

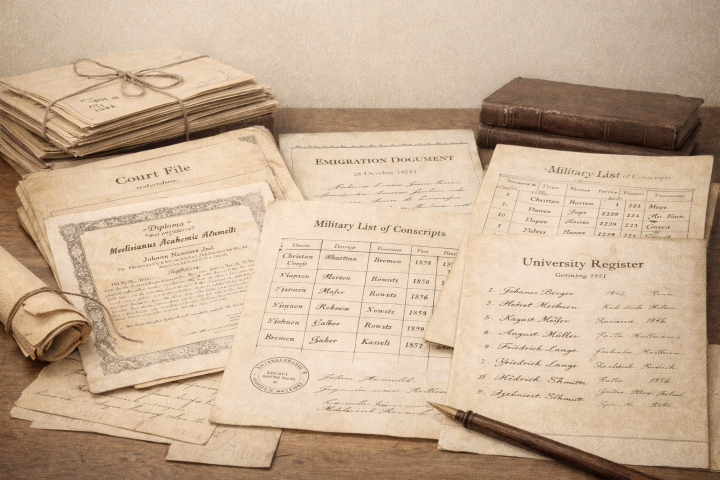

Typical archive-based sources include tax lists, citizenship registers, court files, land and mortgage records, manorial documents, guild records, and local administrative files. These sources are particularly valuable when parish registers have gaps, when multiple families share the same name, or when you need documentary proof beyond vital events.

Archive research often provides the context that turns names and dates into a documented family history: property transfers, legal disputes, guardianship matters, or occupational records can confirm relationships and clarify why a family moved or changed status.

6) Special Record Groups: Courts, Military, Schools, and Emigration

When standard church or civil records are insufficient, we use additional source groups that can contain highly specific personal details. In Central Germany, court records and probate files can be especially informative because they may list heirs, guardians, places of residence, occupations, and property.

Depending on the era and region, we also consult military records, conscription lists, quartering records, school and university matriculation registers, and occupational sources (such as mining, manufacturing, or guild-related records). For emigrants, we analyze both departure-side documentation and destination-side records to connect a person in the U.S. back to their German origin.

These sources are often the key to breaking through “brick walls” because they provide relationships and locality information that may not appear in standard vital registers.

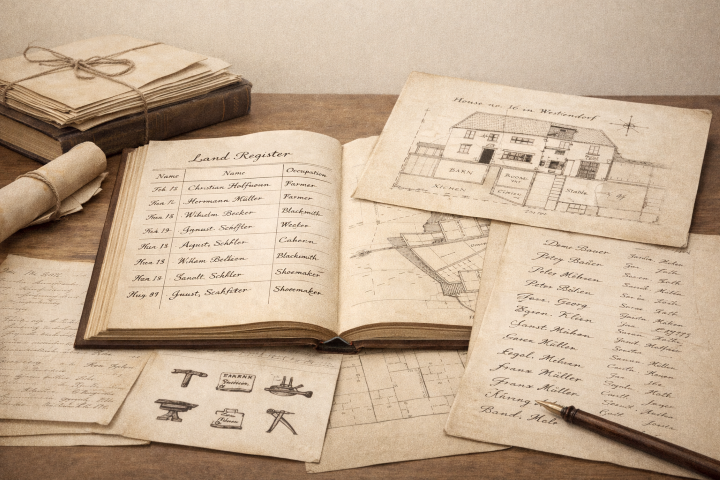

7) Name, Occupation, and Property Research

In Central German research, names and occupations often provide strong geographic and social signals. We evaluate surname variants, dialect spellings, and recurring given-name patterns across generations to distinguish between individuals with similar identities and to connect records reliably.

Occupations can point to specific jurisdictions and record groups—for example, crafts tied to guild systems, or mining and industrial work associated with particular regions. Property and residence research adds another layer: land registers, house histories, and inheritance chains can demonstrate continuity across generations even when records are incomplete.

By combining onomastics (name study), occupational context, and property evidence, it becomes possible to build a more robust proof framework and to turn documentary findings into a coherent and well-supported family narrative.